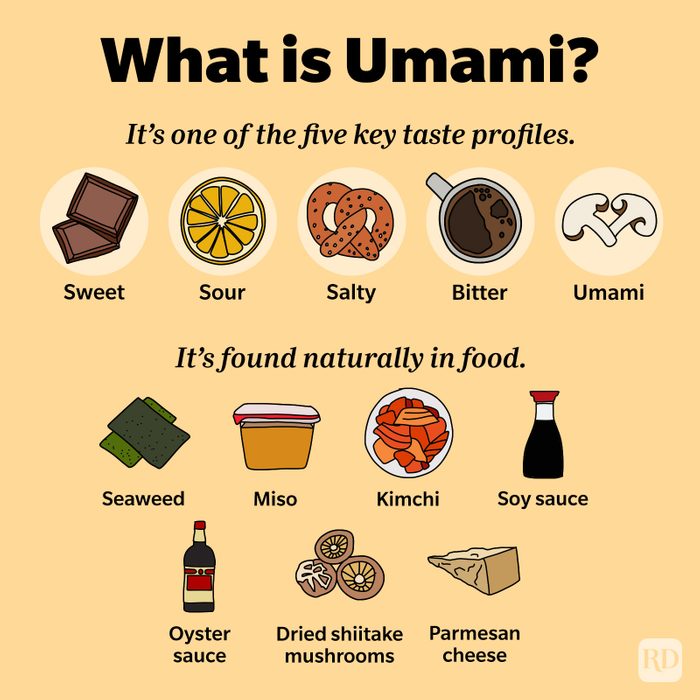

You’re familiar with sweet, salty, sour and bitter. But have you explored umami, the savory fifth flavor?

What Is Umami? 12 Foods with Umami You’ll Want to Try

What is umami?

Most Western traditions identify four basic flavors: sweet, salty, sour and bitter. But there are actually five major flavors! Umami is this fifth flavor and represents the savory, meaty taste that’s in many ingredients and dishes.

When umami-rich ingredients are added to a recipe, they add depth, complexity and a hard-to-describe savoriness that elevate the dish’s flavor profile. Though you might be unfamiliar with umami, you’ve definitely experienced it. Common ingredients like mushrooms, tomatoes and Parmesan cheese are all packed with umami.

What’s the history of umami?

As early as the Roman Empire, people sought ways to infuse their dishes with a fishy, salty, savory flavor. Archaeological excavations have uncovered at least four distinct fish sauces used by Romans in their quest for what we now know as umami. Similarly, the ancient Japanese tradition of producing katsuobushi—a smoked and dried fish essential to Japanese cuisine—aimed for the same flavor enhancement. However, this elusive taste remained unnamed until 1908, when Japanese researcher Kikunae Ikeda isolated and identified it.

Ikeda was intrigued by the unique flavor in his wife’s soups. Through meticulous experimentation, he pinpointed the specific taste molecule: the monosodium form of glutamate present in the brown kelp she used for her stock. This flavor reminded him of meat, dried fish and katsuobushi. He termed it “umami”—the Japanese word for “savoriness”—a name that has endured.

While Ikeda’s discovery wasn’t immediately groundbreaking globally—his research wasn’t translated into English until 2002—it certainly set the stage for umami’s recognition as the fifth basic taste.

What’s the science behind umami?

Just as you think of sugar when you think about sweetness, food experts think of glutamate when considering umami. Glutamate is an amino acid, a building block of protein. Two components come together to create umami: monosodium glutamate (MSG) and disodium inosinate (IMP). These don’t have much flavor on their own, but they enhance umami flavors in food.

It’s interesting to note that the concentration of these compounds varies by food type as well as growing conditions, ripeness, aging and even cooking methods.

For example, vine-ripened tomatoes have more glutamate than tomatoes that are picked green and artificially ripened. Similarly, as cheeses and cured meats age, enzymes break down proteins into free amino acids, including glutamate, that boost their umami over time.

What does umami taste like?

Since umami is complex, it can be a difficult flavor to describe. Food scientists, chefs and home cooks often described it as “savory,” “meaty” or “broth-like.” Notably, umami tends to linger on the palate longer than other tastes, enhancing its appeal. Some studies suggest that adding umami-rich substances can reduce the craving for saltiness in foods. However, excessive umami can overpower other flavors, making a dish taste overly salty or even soapy.

Food historian and scholar Ken Albala experimented with making katsuobushi from scratch to better understand this flavor. He observed, “Umami is actually several different chemicals, often acting in concert,” he says. Arriving at the perfect balance of flavor molecules creates the distinct umami taste.

How do you cook with umami?

“The first step in creating an umami-rich dish is to use quality ingredients that have developed the glutamate and associated chemicals that contribute to umami,” says chef Eric Wynkoop, director of culinary instruction for Rouxbe online culinary school. Sure, you could make katsuobushi from scratch to make umami flavoring yourself, but it’s a labor-intensive dish, and you can buy the ingredient online or at the supermarket. You could also purchase MSG or Aji-no-moto (synthetic MSG), though some folks do not like to use MSG.

Once you’ve collected your ingredients, you can incorporate them into a variety of dishes. Japanese cuisine, for instance, frequently utilizes umami-rich foods. “Umami, whether from kombu (seaweed), MSG or a combination of soy sauce, mirin, sake and salt, is the foundational flavor profile of a lot of Japanese cuisine,” says Gil Asakawa, a cultural consultant and chair of the Denver Takayama Sister Committee.

Layering umami-rich ingredients can create complex and more enjoyable dishes. “When umami is introduced through the layering of ingredients and in balance with the other tastes, the meal is perceived as having depth and providing satisfaction,” Wynkoop adds.

Ready to explore the world of foods with umami flavor? Here are 12 ingredients that naturally contain high levels of umami compounds, making them perfect for enhancing the taste of your cooking.

1. Seaweed

Glutamate content: 170 to 3,380 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

As Ikeda’s original source of experimentation, brown kelp, a type of seaweed, contains the glutamate that gives umami its characteristic flavor. Also known as kombu, edible seaweed’s glutamate content differs by variety, with ma konbu containing more than 3,000 milligrams of glutamate in a hundred grams of seaweed, and rishiri-konbu containing 2,000 milligrams.

Dried seaweed is briefly soaked in warm water to release its umami-inducing flavors; the water is then used to make dashi, a foundational stock of Japanese cuisine. It can be tricky to properly extract the umami without muddying the flavor. According to Elizabeth Andoh, author and Tokyo-based culinary instructor at Taste of Culture, you can delicately extract the best umami from kombu when the water is 60 degrees Fahrenheit. However, if the water warms above 85 degrees, it can become bitter and slimy.

2. Dried shiitake mushrooms

Glutamate content: 1,060 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

A popular additive in many Asian stir-fry dishes, dried shiitake mushrooms pack a lot of umami. And that’s not the case for all mushrooms. Truffles, for instance, only have between 60 and 80 milligrams of umami per 100 grams.

Shiitake mushrooms are very easy to incorporate in almost any dish, are very forgiving toward novice cooks—they’re basically impossible to overcook—and offer a meaty taste and texture without the meat. It is believed that in Buddhist temples, where meat is not consumed, dashi (fish broth made from dried bonito) is created using dried shiitake mushrooms.

3. Soy sauce

Glutamate content: 400 to 1,700 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Fermented products like soy sauce are loaded with umami and enhance the overall flavour of a dish. It’s a go-to ingredient for stir-fries, a wonderful base for marinades and an ever-present side for sushi and sashimi. Some people prefer a Korean soy sauce, while others may choose between Chinese or Japanese soy sauce or tamari. All are great, as they all offer lots of umami, thanks to the fermentation process they go through. The longer the fermentation period, the more intense the umami flavor becomes.

4. Parmesan cheese

Glutamate content: 1,200 to 1,680 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Strong-tasting cheeses like Parmesan—it can take anywhere from 18 to 36 months for the flavor to develop—are high-glutamate foods, which means lots of umami taste. It’s easy to work this ingredient into your favorite meals: Top pasta with freshly grated Parmesan, or sprinkle the cheese over chicken or a healthy salad. For more umami flavor, try Emmentaler, a Swiss cheese with 310 milligrams of glutamate. Or trade your American cheese for cheddar, which has 180 milligrams.

5. Oyster sauce

Glutamate content: 900 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Foodies who love Asian cuisine will recognize this flavorful fermented sauce made by simmering oysters until their juices reduce into a thick, dark glaze. It’s a time-consuming process but it really brings out the natural glutamates. The sauce is rich, flavorful and imparts an umami taste to everything from stir-fried broccoli and eggplant to beef, chicken and fish.

Commercial versions blend oyster extract with soy sauce and other ingredients, but they still deliver that signature umami depth.

6. Tomatoes

Glutamate content: 150 to 250 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Tomatoes are one of the most umami-rich ingredients in Western cuisine. Plus, their umami increases even further when tomatoes are cooked, concentrated or dried. Think, sun-dried tomatoes, tomato paste or slow-roasted tomatoes. They all have amped-up umami characteristics that elevate soups, sauces and stews.

7. Miso

Glutamate content: 200 to 700 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Like soy sauce, seaweed and wasabi, miso is a Japanese staple. It’s a paste made from fermented soybeans and adds depth and a salty, savory flavor to food. It’s the key ingredient in miso soup, naturally. But you can also use it in dressings, marinades and even dishes like sweet potato casserole.

The fermentation period for miso can range from a few weeks to several years. The longer it ages, the richer, more complex and more vibrant the umami flavors become. There are also different types of miso to explore—like white and yellow, which are slightly sweet and light in taste, and the dark, reddish-brown version, which is bolder and punchier. A tiny spoonful of the latter goes a long way in making stews, gravies or soups. They lend incredible depth and richness to any sauce or liquid without overpowering other flavors.

8. Kimchi

Glutamate content: 240 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

This Korean dish of salted and fermented cabbage and vegetables is a brilliant umami-rich ingredient. Bonus: Because it’s high in digestive enzymes, it’s good for your gut. Kimchi is often included in the Banchan course—a collection of Korean side dishes—to stimulate the palette and encourage diners to create their own variations on the dishes they will enjoy. According to the Umami Information Center, kimchi that’s made using napa cabbage yields the highest amount of glutamate.

9. Anchovies

Glutamate content: 630 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Anchovies might be tiny, but they pack a serious umami punch. They’ve been used in various cuisines for centuries, adding depth and complex flavor profiles to everything from sauces to dressings. The way they are cured—with salt and left to ferment—breaks down proteins and amps up the glutamates, creating a deeply savory flavor.

10. Bonito flakes (katsuobushi)

Glutamate content: 30 to 40 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Katsuobushi, also known as dried bonito flakes, is an essential part of Japanese cooking. When you add these thin flakes to hot food, they dance around due to the heat before dissolving quickly, unleashing the hit of umami flavors. While katsuobushi is a must for dashi, it can also be an umami-rich ingredient for other dishes. Just sprinkle it over ramen or roasted vegetables—it’s a game-changer for boosting flavors.

11. Green tea

Glutamate content: 17 to 1490 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Green tea may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of foods with umami, but don’t underestimate it. Green tea—especially Japanese gyokuro—is packed with glutamate, lending it a deliciously savory undertone. There’s also hojicha, or roasted green tea, that is occasionally used in Japanese cooking to infuse broths and simmering liquids. And let’s not forget matcha. Matcha is loaded with umami goodness and works well in both sweet and savory dishes.

12. Walnuts

Glutamate content: 658 mg of glutamate per 100 grams

Walnuts are a common food with umami that can be added to sweet or savory recipes. When added to baked goods or sweet dishes, walnuts add a pronounced umami flavor that balances the dish. If you want to turn up the umami goodness in walnuts, try toasting them before adding them to dishes.

FAQs

What foods have the most umami flavor?

Natural glutamates are abundant in foods such as seaweed, Parmesan cheese, shiitake mushrooms, soy sauce, tomatoes and cured meats such as beef and anchovies.

How do you identify umami in foods?

Umami is often described as savory, meaty or broth-like in flavor. It remains on the palate longer than other tastes and enhances the overall flavor experience of a dish.

Is umami only found in Asian cuisine?

No, umami is present in nearly all cuisines around the world. For example, Italian dishes often feature Parmesan cheese to enhance the umami flavor, while Mexican cooking incorporates tomatoes and dried chiles.

Can umami help reduce sodium intake?

Yes, studies suggest that adding umami-rich ingredients can reduce the craving for salt in your foods, thus helping you enjoy flavorful meals with less sodium.

What are some surprising sources of natural umami?

Some surprising foods with umami flavor include walnuts, green tea, artichokes and sardines. All contain compounds like glutamates or guanylates that contribute to umami.

Is umami the same as MSG?

No. Umami is a flavor, like sweet, sour, bitter or salty. On the other hand, MSG (or monosodium glutamate) is a compound that delivers the taste of umami. Many natural foods also contain glutamates, including tomatoes and cheese.

About the experts

|

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- Ken Albala, food historian and scholar with University of the Pacific

- Elizabeth Andoh, author and Tokyo-based culinary instructor at Taste of Culture

- Eric Wynkoop, director of culinary instruction for Rouxbe online culinary school

- Gil Asakawa, cultural consultant and chair of the Denver Takayama Sister Committee

- The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: “Umami and the foods of classical antiquity”

- Polish Journal of Otolaryngology: “The umami taste: from discovery to clinical use”

- Food Reviews International: “What is umami?”

- The Journal of Nutrition: “Umami and food palatability”

- Flavour: “Seaweeds for umami flavour in the New Nordic Cuisine”

- BioMed Research International: “Umami the Fifth Basic Taste: History of Studies on Receptor Mechanisms and Role as a Food Flavor”

- Umami Information Center: “What is Dashi?”

- Journal of Food Composition and Analysis: “Flavour of Fermented Fish, Insect, Game, and Pea Sauces: Garum and its Modern Implications”

- Japan Forward: “Fermentation: Japan’s Umami Secret Will Make Your Mouth Water”

- Academia.edu: “Garum – Making the Fermented Fish Sauce of the Roman Empire”